Artists: Šárka Koudelová & Martin Chramosta

Curator: Ekaterina Shapiro-Obermair & Wolfgang Obermair

Text: Anežka Jabůrková

Art space: hoast

Address: Große Sperlgasse 25, 1020 Vienna

Duration: 21/11/2025 – 07/12/2025

Šnek, a trace of German sound fossilised in Czech speech, another piece of evidence alongside shared street names, family names, and trade routes that bind people across space. One word pointing to a complexity of relationships that transcend frontiers in a world that constantly draws borders, demarcates, and pigeonholes.

In the joint exhibition of Martin Chramosta and Šárka Koudelová, the snail manifests less as a creature than as a conceptual starting point for thinking about shelter, vulnerability, and form. The shell the snail carries on its back is a symbol of heaviness – we all bear histories, stories, and thoughts that we take with us wherever we go – but also a sculptural principle of building, layering, and repurposing materials, to which both artists return in different ways.

Historically, in the Czech language, “šnek” did not name the animal at all: it denoted a spiral staircase or a screw-like form, a ‘snail shape’ used in architecture and, later, mechanics, before it became the everyday word for the creature itself. The snail-shaped spiral weaves through the exhibition, binding together the works of both artists.

When we enter hoast, our gaze is drawn upwards to a single-channel video composed of two looping sequences of animated photographs, Šnek 1 and Šnek 2 by Martin Chramosta. In one, we encounter a shell-like ornament, a detail from a window grille in Budapest; in the other, a spiral metal element from a garden fence in Basel. At first, these forms appear simple, formal, decorative, yet they are taken from barriers – heavy metal fences that regulate access and protect those inside from intrusions from outside. The video foreshadows the exhibition’s deeper concerns: questions of enclosure, of shutting out or of wanting to disappear. The spiral shape becomes a metaphor not only for the passage of time but also for possible movement: a path that can turn inwards or outwards, that can open up or curl back on itself into closure.

As we move further into the exhibition, we unknowingly become part of Šárka Koudelová’s painting. A small panel is fixed to thin metal rods that curve out from the wall at head height. For the newcomer entering the space, the work first appears from the back as a black form, an odd silhouette. However, its outline is not arbitrary: it comes from a cave opening photographed by the artist. When we look into a cave, we first see only darkness, and our eyes need time to adjust. As a visitor enters the room and we look at them from the back of the space, the painting lines up with their face, so that for a moment the work “Orion” seems to borrow the visitor’s body, since on the other side, the wooden plate holds a face-fragment looking out over a desert, in a light that could be either sunrise or sunset – a moment when it is unclear whether the day is ending or beginning. Across this field, three thin grey-blue lines cut through like provisional paths, translating the snail’s spiral into possible trajectories: moving outwards or turning back in on itself, between fragile optimism and a quiet sense of exhaustion.

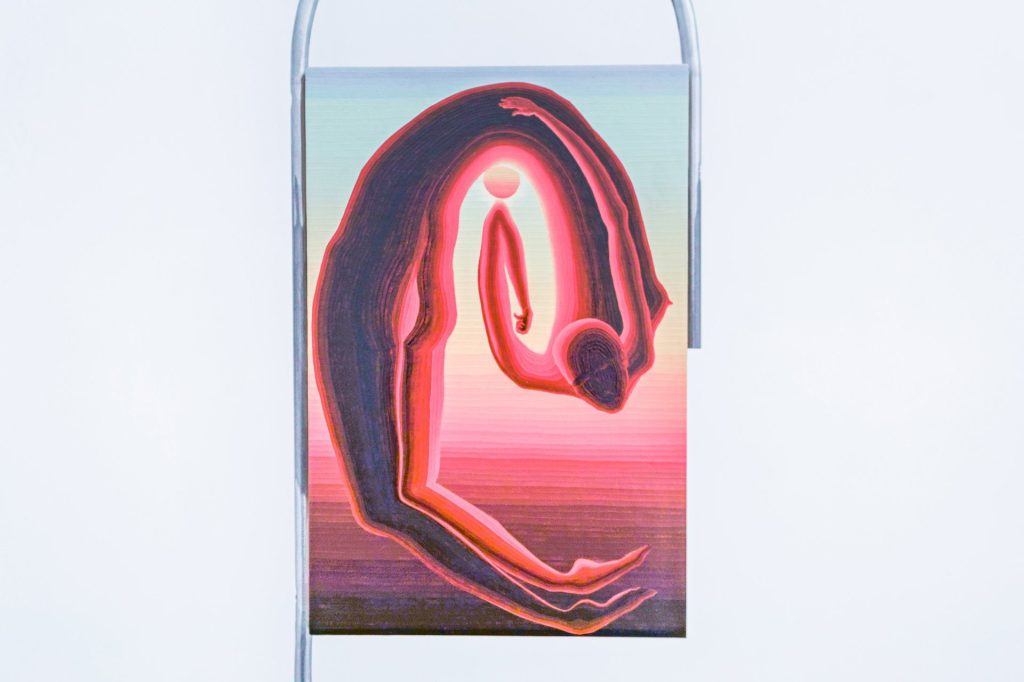

This sense of tentative paths re-emerges in Koudelová’s The Circumstances. Here, too, the painting is mounted on the wall on a thin metal rod, this time extending the spiralling movement. The same motion unfolds within the painting itself, where a female figure floats in mid-air, held in a vortex of images and moments that feel at once intimate and collective. The Circumstances situates us deep inside our own thoughts, in a present marked by constant crisis, anxiety, and suffering. The conditions in which we live shape and determine us, steering us in unanticipated directions that are often hard to bear, and leaving us with a quiet sense of mortality and despair. One possible response to such a state is withdrawal: to curl up, close our eyes and hide. Using a small brush and layering colour line after line, Koudelová builds up the image in a slow, almost meditative process; the dense surface that results recalls the ridged relief of a shell.

The state of being marked by history is also central to the works of Martin Chramosta. He traces decorative elements in architecture, lifts them out of their original environment and places them into a new context, encouraging a different reading and subtly shifting our perception. In this exhibition, both of the elements he works with are taken from fences. In Brno Box, a floral motif on the gate of a bourgeois villa on Žlutý kopec (Yellow Hill) in Brno becomes the basis for an animated sequence: a rapid succession of photographs of the same detail, shown one after another in a raw loop that produces an almost vertiginous effect on the viewer. The video is shown inside a small, house-like structure built from salvaged metal sheets Chramosta has gathered outdoors – a reuse of materials that already carry their own histories, suggesting a quiet animism, as if something more were held within them.

On Červený kopec in Brno (Red Hill), where allotment gardens already occupy land zoned for future housing, the coming residential district is partly present in newly built villas and apartment buildings, and partly only as a plan hanging over the remaining gardens. When part of the colony was evicted and cleared for development, old rusted metal sheets were taken by Chramosta from the site and now form the fragile ‘home’ for the video, a tongue-in-cheek counterpoint to the floral ornament from the fenced villa on Žlutý kopec, recalling plants that have since been destroyed and pushed behind yet another gate. On the slopes of Žlutý kopec, where the bourgeois villas of Masarykova čtvrť (the Masaryk Quarter) overlook the city, the ideal of comfortable private refuge meets the more precarious shelters of garden colonies and improvised structures.

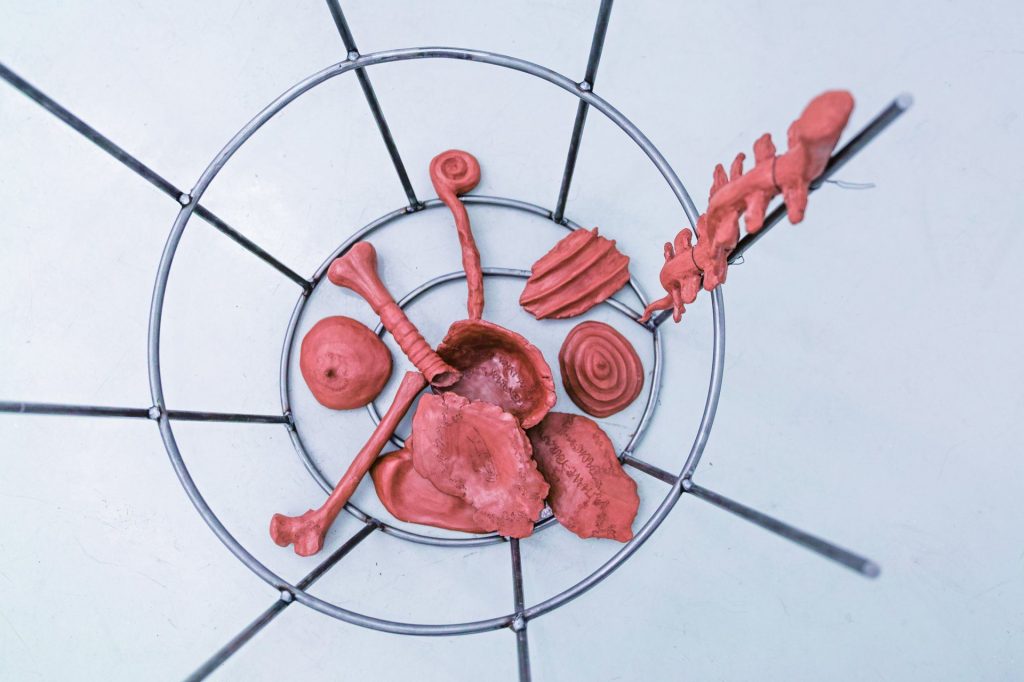

Facing Chramosta’s Brno Box, we encounter Koudelová’s Dismantled Body, a basket-like metal construction. Thin black rods rise vertically like the bars of a fence; at the bottom, a spiral is drawn, echoing the form of a snail’s shell that runs through the exhibition. Inside the structure lie clay body fragments – a body that has been taken apart and redistributed. The basket can be read as a container or cage, as the skeleton of a portable house, but it also stages a choice: whether to follow the spiral inwards, into retreat and hiding, or to trace it outwards, towards movement and contact. The spiral no longer prescribes one direction; it holds open the possibility of stepping out of its curve and assembling something new from these scattered parts.

Ultimately, what links the artistic practices of Chramosta and Koudelová is their shared attention to things often dismissed as merely pretty: ornaments, the sunrise and sunset, decorative or aesthetically pleasing scenes or elements. Their works invite us to enjoy the moment of visual pleasure, and at the same time to recognise the histories, tensions, and vulnerabilities folded into it – to see that behind every ornament and every beautiful view there is a denser, more complicated story.